My new book with Ian Hathaway, The Startup Community Way, is officially out. When I saw the Kindle download first thing this morning, I felt a moment of unbridled joy.

Writing a book is extremely hard. I’ve now written seven of them, all about startups and entrepreneurship. My next one, which I’ve been working on for a year with Dave Jilk (my first business partner), combined entrepreneurship and philosophy. Well, Dave’s been working on it a lot more than I have – I’ve been the slacker in this particular effort. But now that The Startup Community Way is out, and the 2nd Edition of Startup Communities is also out, I’m hopeful that my writing energy will shift to the book I’m working on with Dave.

Some of the inspiration for The Startup Community Way came from Eric Ries. I met Eric in 2007 or so and he’s another example, like Tim Ferriss, of a “good friend and colleague” from a distance. We’ve only physically been in the same space a few times, but I’ve learned an enormous amount from Eric, feel emotionally close to him, and have a deep respect for the work he does.

When Ian and I were struggling with the title for this book, batting around silly things like The Next Generation, my eyes landed on Eric’s book The Startup Way on one of my infinite piles of books. This was his sequel to The Lean Startup, which created the phrase “lean startup” and the lean startup movement.

This was analogous to what happened with Startup Communities. Prior to the first edition, released in 2012, the phrase “startup communities” didn’t exist. The book kicked off a new concept, which is now pervasive throughout the world.

I asked Ian what he thought of The Startup Community Way as a title, partly as an homage to Eric. Ian’s first response was “I like it, but will Eric go for it.” I sent Eric a note and he quickly responded that not only was he supportive of it, he loved it.

At the beginning of 2020, I sent Eric a copy of the draft and asked him if he’d write the Foreword. Again, he quickly responded that he would and cranked out a draft of a foreword that, other than a little editing, we included. He did an outstanding job of connecting the lean startup and startup communities to complex systems. And, he was incredibly generous with his thoughts out linkages and impact between our work.

With Eric’s permission, the Foreword it’s blogged below. I hope you like it and that it inspires you to buy and read both The Startup Community Way and The Startup Way.

In 2020, startup communities, which once appeared on the landscape of business (as well as the literal landscape) like so many rare animals, are long past the point of being uncommon or even unusual. As you’ll read in the many compelling stories of progress that follow, they’re coming together everywhere now, both in this country and around the globe, filled with energy and potential and the desire to look ahead to the kind of future we all want for our society. This is a critically important development. Quite simply: We need entrepreneurs and their ideas to keep our society moving forward, not just economically but equitably. The nurturing of startups, which is amplified by magnitudes when they share in a community of organizations and people, is the best way to make sure we achieve that goal.

That startup communities exist in such abundance is thanks, in large part, to Brad Feld. Every startup is unique, unpredictable, and unstable, but that doesn’t mean they can’t be managed for success, provided it’s the right kind of management. The same is true of every startup community. That’s the subject of Brad’s book, Startup Communities: Building an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Your City. It lays out clear practices and principles for managing the bottom-up (versus top-down) structure of startup communities, which, because they’re built on networks of trust rather than layers of control, can’t be maintained in the same way that public goods and economic development were in the past. Rather than a rigid, hierarchical set of rules and processes, they thrive on a responsive, flexible method of working that uses validated learning to make decisions with minimal error. Like entrepreneurs, startup community builders can’t rely on hunches or assumptions; they need to get out there, gather data, and see what’s happening for themselves. Only then can they bring together diverse, engaged organizations that draw on each other’s energy and experience and are led by committed, long-term–oriented entrepreneurs. By detailing a system that was hiding in plain sight, like so many methods used by entrepreneurs, Brad made it available to anyone worldwide who wants to bring innovation and growth to their city or town.

All of which is why, now that we’ve reached the next phase of startup community development, there’s no one better than Brad to address its central issue: what happens (or doesn’t) when startup communities co-exist with other, more traditionally hierarchical institutions that, as much as they’d like to work with their innovative neighbors, can’t break free of their old rules and management styles? And how can we ensure that all of these players work together with respect for each other’s strengths, and with clarity, to maximize their positive effect on the world around us? Brad’s answer, once again, is to clearly lay out the methods and tools that can affect this change. He and his co-author, Ian Hathaway, have combined deep experience with rigorous, intensive research and analysis to create a framework for this necessary path forward.

Every entrepreneur continues to iterate on their original product, and Brad is no exception. This book, The Startup Community Way: Evolving an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem, isn’t just a follow up to Startup Communities; it’s a refinement of those initial ideas—as well as an expansion of them. It encompasses the increasingly common and often complex relationships and interdependencies between startup communities and legacy institutions including universities and government (both local and federal) and corporations, culture, media, place, and finance. By situating startup communities within this larger system of networks, Brad and Ian shine light not only on the interconnectedness between them, but their connections to the larger community and society as a whole. The Startup Community Way zooms out to look at the big picture even as it provides a close, highly detailed look at each of the actors, factors, and conditions that can combine to create a successful entrepreneurial ecosystem. It also examines some of the mistakes that are routinely made, like trying to apply linear thinking to the distinctly dynamic, networked relationships in startup communities, and trying to control them rather than let them operate freely within thoughtful parameters. All of this is presented with the sole goal of helping to forge deeper connections between often disparate parts so that they can better work together toward a common purpose.

I feel a deep kinship with Brad, whose work echoes in many ways the development of my own thinking about entrepreneurship and its uses. I began with the methodology for building successful individual startups in The Lean Startup and moved on in The Startup Way to applying those same lessons at scale to bring entrepreneurial management to large organizations, corporations, government, and nonprofits. I share Brad’s faith that the entrepreneurial mindset is crucial not just for improving our present day-to-day lives but also for ushering our world into the future as we apply it to all kinds of organizations, systems, and goals, including those involving policy.

One revision Brad has made since the publication of Startup Communities resonates with me in particular: Where he previously called for startup communities to operate on a simple 20-year timeline, he’s changed that to a “20 years from today” timeline. The work of innovation is continuous, and thinking truly long-term is crucial in order to reap its true benefits. What I mean by long-term thinking is an ongoing, honest, and comprehensive consideration of what we want our companies to look like—and our country and our world—for upcoming generations. In order to have the future we strive for, one in which opportunity and assets are fairly distributed, thoughtful management and care for the planet and all of the people who live on it with us is central, and we need to look beyond the right now to the realization of all the promise of the work that’s already been done. This book is a perfect entry point for doing just that.

Eric Ries Author

The Lean Startup

April 2020

Tim Ferriss Podcast: The Art of Unplugging, Carving Your Own Path, and Riding the Entrepreneurial Rollercoaster

Tim Ferriss did one of his very long-form (150 minutes) podcast with me last week. I met Tim for the first time in 2007 and we’ve been friends since, although we’ve spent relatively little time together in person. Like many of my friends, I have a very comfortable remote relationship that has a lot of emotional intimacy in it. While many humans find this difficult, I never have and enjoy it a lot.

I think this comes through nicely in the podcast. It helps that Tim is particularly amazing at the long-form podcast interview. While the setup was around my new book, The Startup Community Way, which comes out tomorrow (please pre-order – authors love pre-orders), I don’t think we talked about the book at all until around hour two!

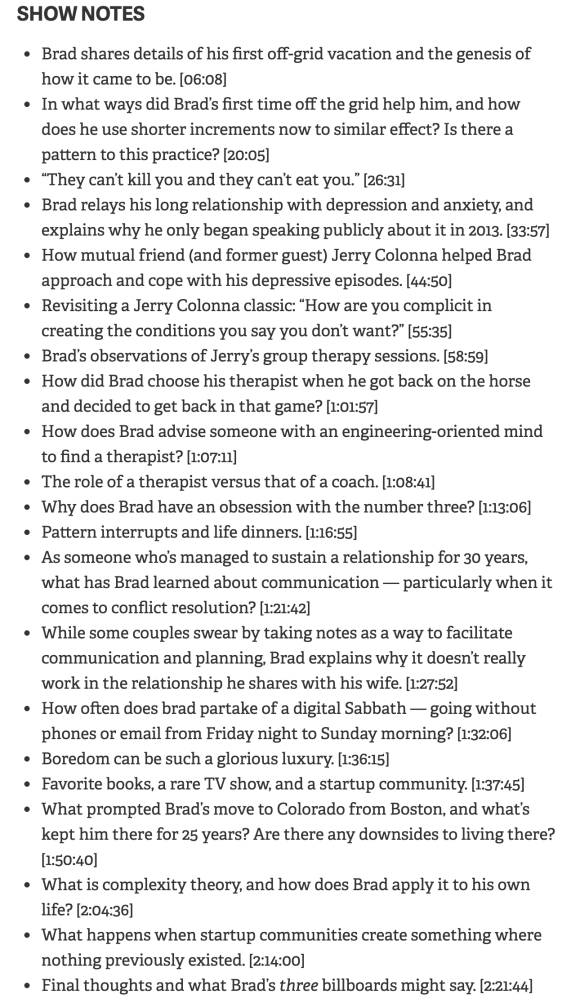

The following are the show notes. I hope you get a chance to listen to this. And, if you have any thoughts or feedback, drop me a note!

Tim – thanks for doing this. I’m honored to be part of your podcast cannon (#448!)

For the last several months, I’ve heard or read the phrase “the new normal” 7,354 times. I’ve steadily grown tired of it and now I believe it is an invalid concept.

There is no new normal. We have move forward and get better.

Steve Case wrote a great OpEd recently titled There’s no going back to the pre-pandemic economy. Congress should respond accordingly.

This week, Congress will likely take up the next steps in the economic response to the covid-19 pandemic. If the package is like previous efforts, it will focus on trying to turn back the clock to February 2020: treating the economy as if it were Sleeping Beauty, merely needing to be awakened to be fully restored. This strategy is a mistake: Congress needs to stop solely backing efforts to restore the old economic reality and focus on how to develop a new one.

The Kauffman Foundation recently came out with a mission to Rebuild Better.

Comprised of more than 150 entrepreneurship advocates across the country, the Start Us Up coalition is working to elevate the voices of entrepreneurs so policymakers reverse decades of misplaced priorities that have made it far easier for big businesses to grow than for new businesses to start at all. Our goal is not just to restore the economy, but to rebuild better by ensuring all Americans — especially female, minority, immigrant, and rural entrepreneurs who have historically been marginalized by investors and lenders — can turn their ideas into businesses.

The goal should not be the new normal. The old normal didn’t work for many Americans. The old normal had incredible income inequity, racial inequity, gender inequity, and many other inequities. When I wrote that I’m Fast-Forwarding to 2025, I had this in the back of my mind, but I couldn’t articulate it.

Change is unpredictable, bumpy, impossible to predict, challenging, stressful, and non-linear. But, as humans, all of these things make us incredibly uncomfortable. Often, we want to go back to “the way things were” since that felt safe, or predictable, or even if we didn’t really like it, was at least something we understood.

Going back to the way we were, with some adjustments, is how I interpret the phrase “the new normal.” I don’t think it will work. I don’t think it’s desirable. I don’t think it’s progress.

So many of the leaders I respect like Steve Case and The Kauffman Foundation are being clear about this. They may use different words, but I feel completely aligned with their vision.

I have no interest in a new normal. I’m only interested in something much better across our society that what was the old normal.

I encourage leaders to embrace change. Embrace complexity. Embrace uncertainty. I certainly am.

We are in the midst of the most dramatic phrase transition I’ve experienced so far in my 54 years on this particular planet.

Ian Hathaway and I talk about phase transitions (also known as a phase shift) in several parts of The Startup Community Way.

Progress is uneven, slow, and surprising. Complex systems exhibit nonlinear behavior, phase transitions (large shifts that materialize quickly), and fat-tailed distributions, where extremely high-impact events are more common than a normal statistical distribution would predict. Seemingly small actions can produce massive changes that happen suddenly. There is little ability to link cause and effect, or to credibly predict the outcomes of various programs or policies.

The Covid crisis is the trigger of this phase transaction. And, if you are a regular reader of this blog, you know that I view the Covid crisis as the collision of four complex systems – health, economic, mental health, and racial inequity. Each of these complex systems has been evolving for a long time, are never “solved”, and come in and out of focus.

The collision of all four of them simply cannot be understood from a macro perspective or addressed incrementally, and is transformative in an unpredictable way.

Easy examples of specific phase transitions include telemedicine, video conferencing, remote work, remote learning, and retail distribution. As this has been happening over the past four months, the entire US macro model around government debt was thrown out the window, resulting in a massive economic value shift (both positive and negative) across our entire economy. At the same time that unemployment is high, but the macro numbers show it “bad, but not awful”, income inequity has soared.

But this isn’t the story of the phase transition. Rather, it’s just the beginning. There are many people on our planet that are hoping things are going to “go back to normal.” The phrase “the new normal” is a hint at that, reinforcing that there is some type of “normal” to expect.

There is no normal, just like there is no spoon.

If you think it’s going to get weird, well, it’s too late. That already happened.

Since March 11th, when I realized the Covid crisis was going to generate a massive phase transition throughout society, I’ve been rethinking everything. Complexity theory teaches us that in complex systems, there is no playbook, just like there is no spoon.

Yet, in our world, we try to apply playbooks to many of the things we do. Many of the things we believe exist run off of playbooks. Take K-12 education. As our society anxiously awaits the opening of K-12 schools in the fall, educators, administrators, teachers, and governments everywhere scramble to “rewrite the playbook” for K-12 in the time of Covid.

But what if the playbook for K-12 is obsolete. Or flawed. Or unnecessary. What if it structurally reinforces undesirable things, like racism or economic inequality?

Observers of the health care system would comment that the health care system in the US has been messed up for a long time. My dad has been writing a blog on Repairing the Healthcare System for a decade. While there is plenty that he writes that I disagree with, I do agree that the healthcare system in the US is structurally broken. And, now with some hospitals in Florida being out of ICU beds, well, hold on to your masks …

We haven’t even begun talking about commercial real estate. My friends in the restaurant industry are suggesting that unless the government sends them a lot of “free money” soon, the restaurant industry as we know it will completely collapse.

Do we need more commercial real estate? Does the restaurant industry, as currently configured, really work?

Regardless of the answers, it’s impossible to predict what things will look like on the other side of this phase transition.

I recently was in an email thread where a Black founder had a powerful and clear response to the question from one of her corporate partners. The question was:

How can our (the corporate partner’s) team better support diversity in our work, particularly in our sourcing, diligence, and onboarding efforts?

The entrepreneur responded with a long explanation that was a brilliant and extremely helpful perspective for me. It follows.

I think one of my core experiences, and a truth that we all have to grapple with, is that programs like yours should be thought of like higher education in 1960, or getting into a NYC Specialized High School today.

Were there no Black students at Harvard because Black people aren’t brilliant? No.

There were no Black students at Harvard because you have to get a certain score on the SAT to get in.

People who score well on the SAT either:

- Come from amazing school districts with a plethora of funding and the ability to prepare students adequately for the test.

- Come from families that can afford expensive SAT prep.

- Come from communities that have an infrastructure that supports robust SAT prep.

Because of institutional racism in our society, Black people:

- Have school systems with a lower tax basis and insufficient resources.

- Make less than half what whites do in many cities and don’t have the resources to sign up for SAT prep.

- Have had our communities and families decimated through mass incarceration and other racist policies.

If we juxtapose that analogy with startups, your team will need to ask itself what criteria you’re using for startups.

Black entrepreneurs have to find a way/make a way/invent a way to launch businesses with two arms tied behind our backs because we don’t get the same funding as our white counterparts.

So I have raised $2.5MM and have to compete with companies who have raised $25m and $70m respectively.

And yet, I’m constantly asked, “What’s your traction?” which is similar to “What’s your SAT score?”

We know that as a society, we are starving Black businesses for capital, and yet we expect them to hit the same milestone markers as businesses that have a plethora of capital. It’s like not feeding a cow yet expecting them to produce milk. It’s literally madness and maddening.

Thinking about your sourcing of Black companies is going to be a far more complex question than “Who do we call to find the amazing Black companies?” It’s going to be “How do we change our lens so we can see the amazing Black companies?” followed by “Once we bring them into our ecosystem, how do we support their journey in meaningful ways that can help to level the playing field = e.g. get them capital or get them revenue?”

Maybe we should stop asking “What’s your SAT score?” and instead ask, “Wow. How on earth did you maintain a 3.7 GPA, and cook for your little brother and sister every night because your mom had 2 jobs, and get an A in calculus without a high-paid tutor, and work a full-time summer job at Key Food while taking a class to teach you how to code at night? That’s a lot of grit!”

Maybe we’re measuring the wrong things in our entrepreneurial society, just as we’ve measured the wrong things in our larger society. Maybe we all need to start talking about grit instead of metrics that can only be achieved with money, and then make sure all entrepreneurs get the funding required to achieve equivalent metrics.

Brooks the Wonder Dog passed away yesterday. Somehow, a long time ago, his vet started referring to him as Brooks Batchelor. Mail came to Brooks Batchelor. His pills, which he took a lot of lately, are labelled Brooks Batchelor. Amy and I giggled everytime we saw this.

Brooks was an awesome dog. He was dog number 3, following Denali and Kenai. Definitely the cuddliest of the three. Always happy. He loved bagels, salmon, and tissue boxes. We ran in Keystone together and did laps around my house at St. Vrain for years until he couldn’t run anymore. He loved chasing bunnies, even if he never caught any. When he was young he loved to swim, but decided that wasn’t for him after he walked straight into the deep end of our new pool on his introduction to our St. Vrain house (we laughed so hard it was challenging to fish him out …)

When Amy and I talk about “Golden Retriever eyes” we are thinking of Brooks. Deep, black, and full of love, especially if you were holding a bagel. Or a piece of salmon.

At some point, he decided he was going to sleep on the bed. Early on we tried to convince him the bed was just for the two of us. I traveled a lot, so when I was gone he slept on my side of the bed. When I was home, he slept at the foot of the bed. Eventually, we got a bigger bed.

When he was a puppy, Kenai took good care of him (Kenai is on the left, Brooks is on the right)

When we got Cooper, he was annoyed for a while. Apparently he forgot that Kenai helped him grow up. Cooper was inscrutable and the first difficult puppy we had. Brooks figured this out before us and, while he’d occasionally assert his dominance, he generally gave Cooper a wide berth. When we sent Cooper to doggie boarding school for a month, we could tell that Brooks didn’t miss him. But, when Cooper came back, enough had changed that they were suddenly (and finally) buddies.

Cooper was extremely patient with Brooks the past few years as Brooks aged. When they ran together with me, Cooper would do his thing for a while but eventually hang back with Brooks who trotted along next to me at my slow pace.

Several months ago Brooks had a seizure. It turned out that he had a significant brain tumor. After being at the vet for a few nights, he came back home and was basically non-responsive. Amy and I cried all weekend, just hung out with him, and were ready to let him go.

We decided to give it one try with the vet where they dialed back some of his meds to see if he could get a few more months. While he still slept most of the time, he was ambulatory, happy, and somewhat responsive when he was awake.

Last Monday he had a series of seizures. Back to the vet he went, where the seizures continued. He passed on Saturday.

I thought of him a lot of my 12 loop run today. I write this with tears in my eyes. Brooks Batchelor, you were a wonder dog. Thanks for being part of our lives.

Colorado now has a statewide mask requirement.

Individuals will be required to wear face coverings for Public Indoor Spaces if they are 11 and older, unless they have a medical condition or disability. Kids 10 and under don’t need to wear a mask. All businesses must post signage and refuse entry or service to people not wearing masks.

It is well understood that wearing a mask substantially helps slow the spread of Covid.

I can’t, for the life of me, understand why the message isn’t getting through. The mask prevents other people from you if you are infected. And, you often won’t know if you are infected, since you could be pre-symptomatic (which is often confused with asymptomatic) for 14 days.

So, let’s keep this simple. You can have Covid, not have symptoms, but be infecting other people for up to 14 days. Wearing a mask significantly cuts down on your spread of the virus if you have it, because the mask catches your spread of the Covid “droplets.”

The mask doesn’t do a lot to protect you from others. So, if you say “I’m not afraid of getting Covid”, that doesn’t matter since the mask doesn’t protect you. It protects others from you. And, you can’t know if you are infectious.

Some people will say “I’ve had Covid so I don’t have to wear a mask.” That’s not true either, for several reasons, including social convention (if we all wear masks, then it’s socially acceptable; there is still ambiguity about how long immunity lasts; there are some concerns, but not scientific evidence, that you can still be a spreader if you think you’ve recovered.)

If you wear a mask, you are respecting your fellow humans. And, if we all wear masks, we can dramatically slow the spread of Covid.

So please, wear a mask.

Multiple times a day, someone in my network asks if I’ll make an intro to someone else. I’m almost always happy to do this and, if not, I will explain why.

I like to do opt-in intros, where I ask the person on the potential receiving end of the intro if they are open to the intro. Most of the time people say yes. Sometimes they say no. Very occasionally they don’t respond to me.

In the past, I’ve written posts about the best way to do this, at least from my perspective (and for me). However, as the number of requests of me increases, the ease and clarity by which people ask for the request has gone down.

So, here’s a new post on the topic, with simple directions that both (a) help make it easy for me, and (b) in my experience, make the ask a lot clearer and easier for the person the receiving end of the request to say yes to.

For the email title, do something like, “Intro to <company> for <mycompany>”. For example, if you are the CEO of Xorbix and you want an intro to GiantBigMonsterCompany, title the email “Intro to GiantBigMonsterCompany for Xorbix”

Write the email “to me” but make most of it about you. Start with something like “Brad, thanks for the offer to intro me to someone at GiantBigMonsterCompany.”

Then, quickly follow with the ask in another paragraph. “I’m interested in talking to GiantBigMonsterCompany about sponsoring the Xorbix conference in July for underrepresented founders.” Include a sentence describing the “why” such as “This is a great opportunity for GBMC to get exposure to an audience of diverse founders.”

Next, write up to three paragraphs, with links, about Xorbix and the specific activity you are addressing

End with whatever you want, including a repeat (in slightly different words) of the ask.

I’ll then forward it with an introduction from me to add credibility and ask if they are willing to connect with you, or ask them to forward on to the right person in the organization to make the connection.

They will either reply with Yes, forward me on to someone else in the organization to see if they are game, say No, or ignore me. The Yes / forward happens about 80% of the time, so you’ll usually get the intro and it’ll have context. And, for me, it’ll take me 60 seconds to do it, rather than a few minutes to put a thoughtful email together.

I have never liked being asked to predict things. I try not to prognosticate, especially around things I’m not deeply involved in.

At this moment, people everywhere make continuous predictions and endless prognostications. At some level, that’s not new, as the regular end of year media rhythm for as long as I can remember is a stream of famous people being asked their predictions for the next year. There are entire domains, such as economics, that are all about predictions. Near term predictions drive the stock market (e.g., future quarterly performance, what the Federal Reserve is going to do in the future.)

As humans, we want to control our present, and one way to do that is to predict the future.

I think the Covid crisis has turned that upside down. As I was reading How Pandemics Wreak Havoc – And Open Minds last night, a few paragraphs at the end hit home.

The first comment is from Gianna Pomata, a retired professor at the Institute of the History of Medicine, at Johns Hopkins University who is now living in Bologna.

Pomata was shocked by the direction that the pandemic was taking in the United States. She understood the reasons for the mass protests and political rallies, but, as a medical historian, she was uncomfortably reminded of the religious processions that had spread the plague in medieval Europe. And, as someone who had obediently remained indoors for months, she was affronted by the refusal of so many Americans to wear masks at the grocery store and maintain social distancing. In an e-mail, she condemned those who blithely ignored scientific advice, writing, “What I see right now in the United States is that the pandemic has not led to new creative thinking but, on the contrary, has strengthened all the worst, most stereotypical, and irrational ways of thinking. I’m very sorry for the state of your country, which seems to be in the grip of a horrible attack of unreason.” She continued, “I’m sorry because I love it, and have received so much from it.”

It’s followed by a comment by Lawrence Wright, a staff writer at The New Yorker since 1992 and author of the incredible and timely book The End of October.

I understood her gloomy assessment, but also felt that America could be on the verge of much needed change. Like wars and depressions, a pandemic offers an X-ray of society, allowing us to see all the broken places. It was possible that Americans would do nothing about the fissures exposed by the pandemic: the racial inequities, the poisonous partisanship, the governmental incompetence, the disrespect for science, the loss of standing among nations, the fraying of community bonds. Then again, when people confront their failures, they have the opportunity to mend them.

These paragraphs reflect the reality that I’m observing in the US right now. However, you can see Wright’s human optimism creep in as he “[feels] that America could be on the verge of much needed change.” While not a prediction (thankfully), it raised the question at the end of the paragraph, which is:

“[W]hen people confront their failures, they have the opportunity to mend them.“

But how?

As I worked on The Startup Community Way and got my mind into how complex systems work, I concluded that change has to come from the bottom up, not the top down. While in the book, we apply it to startup communities, I’ve internalized it across any complex system.

We are living in the collision of a series of complex systems that are beyond anything I’ve experienced in my 54 years on earth. It’s happening against the backdrop of instantaneous global communication, which allows anyone to distribute and amplify any sort of information.

In a crisis, anger and fear generate irrational behavior, especially given the need to control things. History has taught us this, but all you need to do is watch the bad guys in popular movies implode to be reminded of it.

Consequently, predicting the future is not just impossible; it’s more irrelevant than ever. Fantasizing about what the future will look like, while comforting, is pointless. And anchoring hopes around the future (e.g. “schools will open up in the fall”) simply generates even more anger and fear if it doesn’t come true.

For many years, I’ve tried to avoid predicting the future or prognosticating about it. My answer, when asked, is often some version of “I don’t know, and I don’t care.”

I think this crisis has shut that off entirely for me, as I’m shifting all of my energy to the present. I’m focusing on doing things today that I believe in, want to do, and that I think has the potential to impact positive change. But I know I can’t predict the outcome of any of it.