Month: May 2019

I was at a board meeting last week that introduced something new into the mix that I thought was brilliant.

At the beginning of each section of the board meeting, there was one slide that was titled: “What Are We Trying To Get Out of This Section.” Before we started into a section, whoever was leading it walked everybody in the room specifically through what she was expecting to get out of the section.

I think we did this five times over a 3.5 hour board meeting. The first time it felt a little pedantic, but by the last time it was clearly magical. Each “What Are We Trying To Get Out of This Section” was different. Sometimes it was a decision. Other times it was feedback. Once it was a set of introductions.

You could feel the people in the room get recalibrated whenever this slide came up. The previous section had come to an end. The new section hadn’t yet started. Take a deep breath. Erase all the noise in your brain. Pay attention again, especially if your mind has drifted because of the bloviating of the Boulder-based long-haired board member.

I’d never seen this particular tactic before. I hope to see it again.

I read Ben Horowitz’s The Hard Thing About Hard Things last weekend. This is the third time I’ve read it. It gets better each time. If you are a CEO and you haven’t read it, buy it right now and read it next weekend.

There are endless gems in the book, many of them from Ben’s own experience. My favorite of all time, that stays with me through all the work I do, is his distinction between “peace time” and “war time.”

I think the first time he wrote about this was in his post in 2011 titled Peacetime CEO/Wartime CEO. There has been plenty of commentary on the web about it (see The Myth of the Wartime and Peacetime CEO, which really only says a CEO has to be effective in both wartime and peacetime to be successful.)

Ben has an incredible rant in the post that starts off with:

Peacetime CEO knows that proper protocol leads to winning. Wartime CEO violates protocol in order to win.

The rant is worth reading every single word, but I want to highlight and comment on a few of my favorites.

The first one is:

Peacetime CEO always has a contingency plan. Wartime CEO knows that sometimes you gotta roll a hard six.

BSG fans know about rolling a hard six even though the definition is contested by pilots who think non-pilots confuse planes with dice. In wartime, the odds are often very against you. Sometimes you just have to get lucky.

Another one that I love is:

Peacetime CEO strives for broad based buy in. Wartime CEO neither indulges consensus-building nor tolerates disagreements.

Things during wartime are intense. Decisions have to be made quickly. Many will be wrong, need to be overturned, and new decisions have to be made. Sitting around arguing about what to do simply doesn’t work. Get all the ideas out on the table, but then choose. And then execute like crazy.

Finally:

Peacetime CEO sets big, hairy audacious goals. Wartime CEO is too busy fighting the enemy to read management books written by consultants who have never managed a fruit stand.

Your big hairy audacious goal in wartime is not to die.

As an investor, I’m involved in some companies operating in peacetime and others in wartime. There’s a lot of emotional dissonance during the day as I go back and forth between them. I’ve learned how to be calm in both modes and deal with my emotions outside the context of interacting with CEOs, founders, and leaders. But, Ben’s metaphor of peacetime vs. wartime has been so incredibly helpful to me as an investor in identifying what mode I’m in that I should probably get him some sort of a gift as a thank you.

In February 2017 I met Shawn Frayne, one of the founders of Looking Glass Factory, a Brooklyn-based company with ambitions to make holographic interfaces a reality. Their team was scrappy and had sold an impressive variety of volumetric display kits to fuel their R&D efforts, and since our human-computer interface investment theme is one of my favorites, we led their Series A round.

Last summer they launched their flagship product, a dev kit called the Looking Glass. It was the first desktop holographic display to come to market for, well, extreme nerds (like yours truly) that have been hoping for holographic displays their/our whole lives.

The Looking Glass dev kits and the adjoining Unity and three.js SDKs sparked a wave of holographic app creation over the past few months, with thousands of hologram hackers creating new and wonderfully weird apps in their Looking Glasses every day. Looking Glass clubs are even springing up, like this one that meets in Tokyo with a few hundred members and growing.

But these systems are strictly dev kits, meaning they require the user to have a powerful computer to connect to and run the holographic display. I have several Looking Glasses of my own and I love them, but most of the time they sit idle because they can’t run standalone. The multitude of holographic apps being created by developers around the world, like holographic CT scan viewers and interactive software robots and volumetric video players for the Looking Glass, haven’t really been deployable outside of a highly technical crowd that already owns powerful computers.

That changes today with the launch of the Looking Glass Pro, an all-in-one holographic workstation. The Looking Glass Pro is a turnkey holographic solution for any enterprise that needs to display genuine 3D content to groups of people without subjecting them to the indignity of donning a fleet of VR headsets.

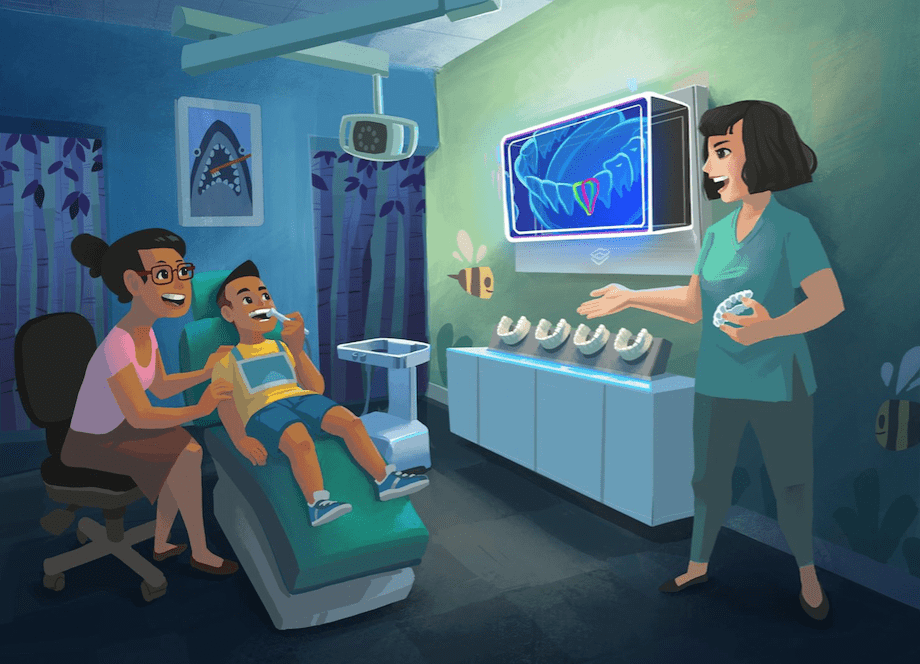

Some first use cases are showing up in fields like orthodontics, where holographic renderings of dental CT-scans for surgeons (and soon for patients) are fast becoming a reality.

In situations where agencies are generating things like volumetric music videos and holographic ads (like in the case of Intel Studio’s production Runnin’, generated by Reggie Watts and written and directed By Kiira Benzing), being shown at the Augmented World Expo this week in a Looking Glass Pro).

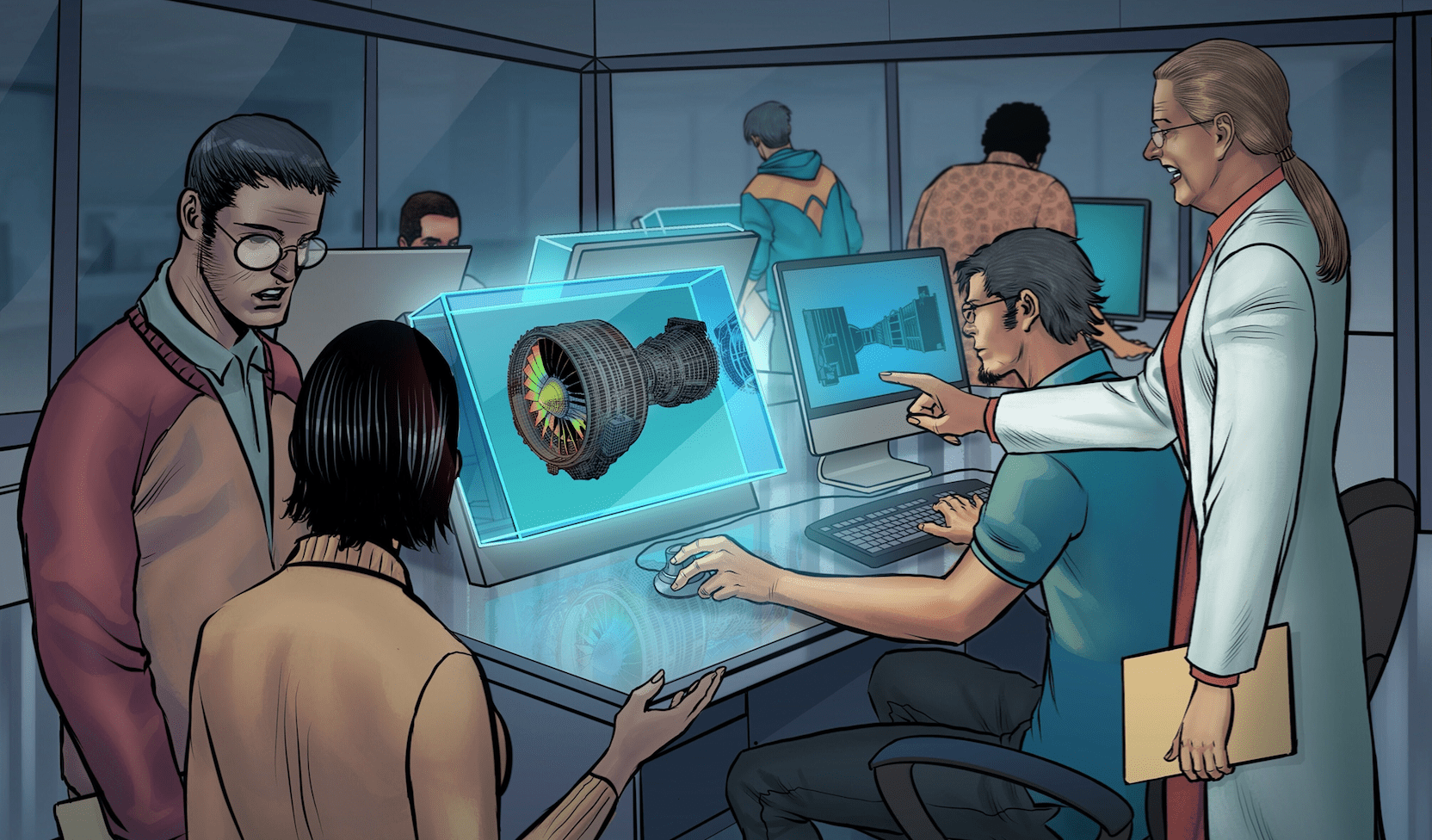

And in scenarios where groups of engineers need to review three-dimensional simulations of phenomenon like the mechanical stresses in to-be-printed parts and complex biological systems in the Looking Glass Pro as if they were viewing the real thing.

The Looking Glass Pro comes with a lot of built-in functionality, including a powerful embedded computer, a direct touchscreen on the holographic display for interacting with the 3D content, and even a flip-out 2D touchscreen for things like text entry and extended UI. Most importantly, the Pro comes with a commercial license to the Holographic Software Suite, a collection of the Looking Glass SDKs for Unity, three.js, and the newly announced Looking Glass Unreal Engine SDK, meaning developers in the enterprise can make apps for the Pro and deploy them fully-standalone for commercial applications for the first time.

This story has been told before, where a new computing platform makes the phase change from a dev kit for a group of technology enthusiasts into something that businesses can use. Think back to the Apple I’s transformation into the Apple ][ series, the evolution (several times over) of 3D printers, or even AR headsets if what Hololens 2 and just-announced Google Glass 2 are doing is any indication.

The launch of the Looking Glass Pro is a sign that that time has come for holographic interfaces.

If you’re an enterprise looking to get into the hologram game, get one of the first batch of Looking Glass Pros today before they sell out.

Imagine that when you were a kid, someone told you that your dreams are important for the world and that what you do matters right now.

Now, match that with an epic adventure of creating future realities, throw in rockstar mentors, entrepreneurship skills training, tech, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, and you have Dream Tank.

Big things happen when someone imagines an awesome new reality. While adults can do this, we are often stuck in a system that is limited in its thinking and driven by incrementalism. We are oppressed by the now, rather than inspired by what could be.

Kids see things in a different way. Take a look at the student climate strike that a 16-year-old girl in Sweden started. Greta Thunberg, who is currently on the cover of TIME magazine, started striking from school on Fridays last fall. She started a movement where 1263 strikes happened in 107 countries last Friday, May 24. The message is clear: why should I be studying for a future I won’t even have, so let’s take collective action now!

Dream Tank is a summer program designed for kids and teens who want to launch and implement their ideas to address real-world challenges. Like many other entrepreneurial things I’ve been involved in, it has its roots in Boulder. It is currently expanding to offer year-round accelerator-for-kids-and-teens programming through summer camps, after-school programs, and a homeschool program for teens.

This summer, Dream Tank has partnered up with different Boulder institutions such as the Museum of Boulder, The Riverside, Niche Workspaces, and Peregrine Crypto Cafe to create specific activities for different interests. Each program is designed for kids to choose a social or environmental issue they want to address. All of the summer programs end in a demo day event where the community is invited to listen, support, and partner with the kids.

Amy and I support Dream Tank because we want to support radically innovative new ideas for the future. If you want your kid or teen to have a voice, have fun, and learn some tools that can make their dreams a reality, sign them up for a summer camp at Dream Tank.

I have awful handwriting.

I used to not care, but at age 53, I find myself writing on paper more than I have the past 30 years. I’ve decided that I’m going to improve my handwriting because I think it will increase my joy of writing on paper.

I’ve always rationalized that my bad handwriting comes from being the son of a doctor who has terrible handwriting, being left handed, and spending most of my time typing instead of writing on paper.

But that’s nonsense. I’m also the son of an artist who has beautiful handwriting. I’m married to a woman with delightful handwriting. I learned to type in sixth grade and have been practicing ever since in direct contrast to writing by hand, which I mostly avoid.

One of my summer projects is to improve my penpersonship (why is it called penmanship – what a silly word which apparently peaked around the 1930s.)

Handwriting is such a better word.

I started my journey with Google and quickly discovered 8 Tips to Improve Your Handwriting and How to Improve Your Handwriting in 30 Days: The Challenge.

Fortunately, that led me to a bunch of books which I bought, including:

- American Cursive Handwriting

- Spencerian Penmanship

- Spencerian Handwriting: The Complete Collection of Theory and Practical Workbooks for Perfect Cursive and Hand Lettering

- Improve Your Handwriting

- The Power of Letterforms: Handwritten, Printed, Cut or Carved, How They Affect Us All

I also bought a bunch of green Pilot G2 Retractable Premium Gel Ink Roller Ball Pens since one of the things I saw online said: “the pen is important and this is my favorite one.”

If you have suggestions for how to improve one’s handwriting, I’m all eyes (and ears, and hands …)

Michael Natkin at Glowforge recently wrote a great post titled Strong Opinions Loosely Held Might be the Worst Idea in Tech.

I have never liked this entrepreneurial cliche. While I have a large personality, I don’t have a temper and I’m not argumentative. I try hard to listen (although I’m not always great at it), try to express my thoughts as “data” rather than “opinions”, and try to evolve my thinking based on the inputs that I get.

I’ve always felt that people who had “strong opinions loosely held” (SOLH) were simply being bombastic. Sometimes I could see that they were being provocative. Occasionally I’d give them credit for changing their mind about something based on new data. But usually, I discount their first opinion (or assertion) since I knew they didn’t have much conviction around it.

Michael’s post opened up an entirely new way for me to think about this, and to continue to dislike SOLH. He has two magic paragraphs in the post. The first is the setup:

“The idea of strong opinions, loosely held is that you can make bombastic statements, and everyone should implicitly assume that you’ll happily change your mind in a heartbeat if new data suggests you are wrong. It is supposed to lead to a collegial, competitive environment in which ideas get a vigorous defense, the best of them survive, and no-one gets their feelings hurt in the process.“

There’s that word bombastic again. Hang on it to it while we get to the punchline of Michael’s post.

“What really happens? The loudest, most bombastic engineer states their case with certainty, and that shuts down discussion. Other people either assume the loudmouth knows best, or don’t want to stick out their neck and risk criticism and shame. This is especially true if the loudmouth is senior, or there is any other power differential.“

Unless the other people in the room are also bombastic, the discussion shuts down and the strong opinion loosely held is accepted, or at least reinforced. Power dynamics amplify this – if the leader is bombastic, head nodding ensues. If you are an underrepresented minority in the room, challenging the SOLH can be even more difficult.

Even if, as a leader, you have tried to establish a culture of challenging everyone’s’ opinions, the loudest, most forceful, and most assertive person in the room will often have the leading opinion. It’s exhausting, at least for some of us, to have to fight against that.

I’m not even sure that a “strong opinion loosely held” qualifies as something useful. I’m fine with “strong opinions supported by data and experience.” I’m less good with “strong opinions supported by belief” as I don’t really know what underlies “belief” for many people. But it’s the loosely held part that I struggle with.

Basically, a SOLH is simply a hypothesis. If someone says to me, “I have a hypothesis”, I assume they are asking me my view about their hypothesis. So – when someone presents me with a SOLH, you’ll often hear me ask “do you think that is the truth or is that a hypothesis?” I’ve found this pretty effective for breaking through the LH part.

Michael’s article has a gem in at the end about how to interact with the SOHL person that he goes through in the final section called This (Actually) Won’t Hurt A Bit. I won’t spoil it for you – go read it.

If the majority of your understanding of how tariffs work is from Twitter, CNN, or Fox News, I encourage you to go read Trump’s China Tariffs Hit America’s Poor and Working Class the Hardest. And, if you think China is paying the U.S. directly for the tariffs, well, no …

We have a lot of hardware companies in our portfolio so I’ve been living in the world of “what to do about tariffs” for several quarters. My fantasy at the beginning was “ignore and hope they go away.” This quickly evolved through “are there any ways around this” to land at “deal with the reality of increased cost, research, and compliance.”

Fun.

It also became apparent, almost right away, that startups had a huge disadvantage over larger companies that had significant U.S. lobbying activities. We explored a few paths to engaging with the U.S. government around this and basically were told some version of “go away – you are too small and unimportant.”

Awesome.

Once I accepted the reality that the startups were going to have to pay the tariffs directly, that they had little control on what the tariffs would be, how and when they would change, and whether or not they’d get exemptions, I started operating under the assumption that 100% of the cost associated with the tariff would fall on the startup.

So, I started observing what other companies, especially large ones, were doing beyond the lobbying efforts of BigCo that resulted in exemptions. Would they absorb the tariff as an increase in COGS? Would they increase prices? Would they pass on the tariff to the customer?

A little more research showed what is pretty obvious in hindsight. Many BigCos are simply treating the tariff like a tax and passing it on, either directly or indirectly, to the consumer. This is similar to what is happening with state taxes, as states come up with lots of new taxes for out of state vendors, both physical and digital.

This shows up a few ways. While some companies are increasing the cost of their product to include the tariff (or even a markup on the tariff), many companies are trying to hold their price the same while passing the tariff on through other approaches.

Some companies are adding a line to their invoice called “Tariffs” and charging that to customers (I’m seeing this mostly in B2B situations). This looks like:

Product Price: $X

Shipping: $Y

Tariffs: $Z

Taxes: $T

——————–

Total: X + Y+ Z + T

Others are including Tariffs in the Shipping line.

Product Price: $X

Shipping and Tariffs: $Y + $Z

Taxes: $T

——————–

Total: X + Y + Z + T

But the one I’m seeing the most is simply including Tariffs in the “Taxes” line, where Tariffs are considered a tax.

Product Price: $X

Shipping: $Y

Taxes: $T + $Z

——————–

Total: X + Y+ Z + T

While some BigCos appear to be eating the cost of the tariff, this seems to be the exception. Startups should pay attention, and act accordingly.

If you are a hardware startup and have either seen, or figured out, a different approach, I’d love to hear about it.

CSbyAll: An Interactive, Crowdsourced Timeline of the CS Education and Diversity in Tech Movement

The modern computer science education movement, commonly referred to as Computer Science for All or #CSforALL, has been gaining momentum nationwide since 2004 and is poised to be the most significant upgrade to the US education system in history.

History is recorded and codified through the journalism, social media, and public policy, and tends to emphasize the voices of those already in the public eye. Moreover, we know that media frequently amplifies the loudest voice in the room, and often misses the contributions of those without social capital and power, including women and minorities. Recent films like Hidden Figures and The Computers show this phenomenon by documenting the lost history of women’s contributions to engineering and technology fields.

Unfortunately, reporting on the Computer Science for All movement is already showing evidence of the erasure and dismissal of the contributions of educators, and in particular women and minorities.

On March 3, 2019, 60 Minutes ran a segment on increasing girls’ participation in computer science that excluded the contributions of all of the women-led organizations working to increase girls’ involvement in tech. The segment credited Code.org with solving the problem “once and for all,” sparking nationwide outrage and pushback from community stakeholders including Girls Who Code, littleBits, AnitaB.org, NCWIT, and CSforALL.

Even more damaging, the 60 Minutes piece incorrectly claimed that the number of women majoring in computer science has declined. The number of women receiving undergraduate degrees in computer science has quadrupled since 2009 thanks to efforts of organizations like the National Center for Women & Information Technology, CSTA, and AnitaB.org, as well as investments by the National Science Foundation, Microsoft, Google, Apple, and many others over the past decade.

I was excited to watch the 60 Minutes piece and wrote a quick blog post titled littleBits Is Helping To Close The Gender Gap in Technology with a teaser about it. I then watched the whole episode and was incredibly upset. I fumed for a while and then emotionally supported several women, including Ayah Bdeir, littleBits CEO, who wrote An Insider’s Look at Why Women End Up on the Cutting Room Floor.

I wrote a draft of a blog post but realized that it wasn’t additive to the discussion. I was mad at 60 Minutes, felt incredibly frustrated, and was sad for all the women who were once again marginalized by the way things were portrayed.

I’ve been living in this problem since 2004 when I joined the board of a nascent organization called the National Center for Women & Information Technology (NCWIT). I’ve learned an incredible amount about gender issues in technology – and in general – from working alongside Lucy Sanders and her wonderful organization since then. I’ve tried to be the living embodiment of a male advocate (now commonly referred to as a male ally) and, while I’ve made plenty of mistakes over the years, have been on a learning journey that has made me a much better human.

When Ruthe Farmer, the Chief Evangelist for CSforALL (and formerly of NCWIT) reached out to me about helping with a new project called CSbyALL, I immediately said yes. Amy and I have been supporters of CSforAll for several years and count a number of the board members as friends, especially Fred and Joanne Wilson who helped get CSforAll up and running.

Amy and I, along with Fred and Joanne, are proud to be the first contributors to this new project to document the actual history of the modern computer science education movement. CSbyALL will be a crowd-sourced interactive timeline and data visualization tool that will surface and illuminate the collective stories, artifacts, and events from the distributed CS education community. It will recognize the contributions of not only national leaders and policymakers, but also local advocates like teachers and school administrators, out-of-school time educators, local organizations, and researchers.

If you are interested in supporting this effort or getting involved in any way, drop me an email.

I had surgery recently and a few friends, including Chris Moody and Sarah Ahn, gave me some books as gifts. They knew I’d be spending a lot of time on the couch either napping or reading, so my pile of infinite books to read became more abundant with a few good ones including The Moment of Lift: How Empowering Women Changes the World by Melinda Gates.

While I’ve met Melinda’s husband Bill a few times, but I’ve never spent any time with Melinda. I know plenty of people who know her or work for her and have overlapped with a few organizations that we both support. However, after reading The Moment of Lift, I feel like I now know her. And, she is awesome.

The book is a combination of a memoir, a manifesto, a case study, and a roadmap. While it uses the backdrop of empowering women as the framework, it genuinely addresses how empowering women can change the world.

In the current entrepreneurial climate of “changing the world” and “making a dent in the universe”, this is the first book that I’ve read in a while that really hit home on these issues. I’ve felt discouraged recently by the tenor of the entrepreneurial discussion, where phrases like “changing the world” have become cliches and are really an entrepreneurial proxy for “making a lot of money.” While I don’t object to that, I get tired of the optimistic language as a shield, rationalization, or misdirection for the real underlying motivation.

Melinda turns this on its head in The Moment of Lift. The examples she gives are real examples of changing the world through foundational activities for women, mostly led by women, and supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. She devotes a chapter to each of the following topics:

- Maternal and Newborn Health

- Family Planning

- Girls in Schools

- Unpaid Work

- Child Marriage

- Women in Agriculture

- Women in the Workplace

Buried in the middle of the book is an intensely personal chapter about Melinda’s own journey. Her level of self-awareness, humility, and discovery reinforced her awesomeness, and created my own moment of lift while reading the book.

Melinda, both personally, and through her work with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation inspire me. It was a perfect book to read while healing. Thanks Chris and Sarah for the gift.